Post-Mortem: Why My Startup Failed

In 2011, I took a 4-month sabbatical from my job to reflect on life. This led to me leaving the job and leaping into the unfamiliar and unglamorous life of an entrepreneur. My first project, Club Ovahi, was a failure.

I was recently inspired by the Without Fail podcast to reflect on exactly what happened and why things turned out the way they did. The simple reason on why Club Ovahi failed was that we f**ked up. That’s it. If this satisfied your curiosity then thank you for reading and see you later. If you’d like a bit more detail then please read on.

Club Ovahi was conceived in the summer of 2011 after a few months of brainstorming sessions with anyone who was willing to participate. I bought a whiteboard, invited people over to my place over pizza, met folks in coffee shops, read books, and attended meetups until I stumbled into an idea that kept me excited and going. It was a mobile loyalty app that would digitize the paper punch card (e.g. buy 10 get 1 for free). Very simple and hadn’t been widely done at the time. Certainly not in Toronto.

After incorporating in early 2012, the first version of the Club Ovahi app was launched and I went through the grueling process of adjusting to a life of uncertainty, low/no income, and walking the streets to convince independent merchants to adopt the app. A far cry from the daily grind in a Big Four office. About the same time, my buddy, Ahmed El-Kadars, joined forces with me and became a co-founder. I remember vividly, one night, waking up anxious and short of breath, Ahmed was kind enough to take me for a drive around town to help calm me down. Yeah, the sh!t was real.

After a couple of years of trials and a pivot, I accepted Club Ovahi a failed business in early 2014. So what went wrong?

The pain point that wasn’t really painful

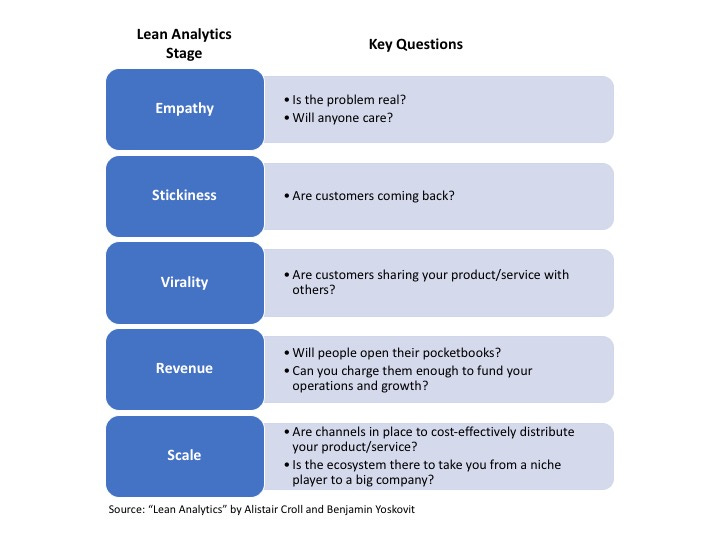

In their book Lean Analytics, Alistair Croll and Benjamin Yoskovit define 5 stages that a startup should go through:

I found the five stages to be especially applicable for disruptive innovations. Disruptive in the sense that they require some change in user behavior. In contrast, sustaining innovations are upgrades of existing products or services.

The mistake that we made is that we never properly graduated from the Empathy stage, however, we kept on trying to generate revenues and scale! We kept on haphazardly jumping around the different stages.

The Empathy stage is a deceptive one. It’s tricky to navigate. It’s very subjective and is dominated by emotions and biases. We thought we had a solution to the pain of carrying physical stamp cards in your wallet and misplacing them all the time. Wouldn’t it be nice for someone to have their card inside their phone and never think “oh dang, I lost the card!”. We also believed that independent merchants would happily accept a digital loyalty platform that would give them some additional customer data and reports. Who wouldn’t?

It turned out that even though the pain was real, it wasn’t enough of a pain. This is a very important point. We demanded that our users download the Club Ovahi app, sign up, and launch the app plus scan a QR code every time they order a coffee at the point of sale. These actions added friction, they added precious seconds or even a few minutes to the terrible experience of waiting in line (not to mention fumbling to launch the app while simultaneously paying in cash or with a credit card). These frictions were not outweighed by the solution to the pain. Plain and simple. When we should’ve realized this fact and either changed course or in Silicon Valley style, “failed fast”, we kept on going. Trying to scale against the odds and generate revenues.

Independent merchants, on the other hand, simply didn’t have the time or capacity to manage a new customer management system. They are overworked and stressed. The last thing they want is a new portal to manage loyalty. The paper punch card was simple and didn’t have that portal. We asked for too much from them and the fancy loyalty research and academic papers didn’t measure up to the daily realities of the shop owner who’s juggling a million things.

Wrong signals

So why did we keep on going for almost 3 years? We focused on the wrong signals:

Diehard users who were using the app on an almost daily basis (well into 2017!): A few users who love the idea are not enough to sustain any business. There is no magic number of users, but an early stage business that’s on to something should be feeling a “pull” from their user base. In Lean Analytics, Croll and Yoskovitz emphasize the need to identify the one metric that matters and to run away from vanity metrics. A few diehard users were a vanity metric.

App downloads: Another vanity metric is the number of app downloads. Early on we had thousands of them. Early stage entrepreneurs are easily deceived by this metric, but in reality, it means nothing. Think about how many times you’ve downloaded an app, only to quickly relegate it to oblivion.

Crazy competition: In Toronto, a lot of punch card digitization startups popped into existence. We all did the exact same thing, and the funny (and sad) thing is that we’re all out of business. I’ll name a few: Ferret Card, Nifty, Triumf, and Collectr. There were others that I can’t remember. Even the mighty Rogers competed against us with their Vicinity product. That also failed. The good thing about competition is that they kept us sharp, the bad thing is that they rushed us to scaling activities before we got comfortable with the Empathy and Stickiness stages. The competition also served to validate that our idea was viable.

A grant and a business loan: The grant and business loan we received inadvertently validated our idea and gave us steam and cash to continue down the same path. We did receive an online (and useless) critique of our business plan along with the grant, but that didn’t change the fact that they gave us the money. The business loan came attached to a coach who was also useless and a time waster. As a taxpayer, I demand a reform of our grant systems!

Examples from the US market: Learning from other markets is always a good idea. We tracked a couple of high octane punch card startups in the US. One was Punchd which got acquired by Google, the other is Belly Card which had a lot of funding from Andreessen Horowitz and other prominent VCs. Our take was that it’s a no-brainer to run a similar business here in Canada. I presume that our competition thought the same way. But here’s the thing, we have no way of truly telling if the US companies were successful. We didn’t have access to their financial statements or metrics. The fact that they got acquired or raised a hell of a lot of money is not an indicator of customer success. Also, customer habits are not the same between markets. Another painful lesson we learned.

The pivot and running out of steam

We managed to white label and sell (yes, for money) a white-labeled version of the app. This was to a large FMCG. The promise was that we would introduce loyalty to FMCG products. The market value was irresistible, so that was the approach that we took. But the long sales cycles of large clients killed us. We ran out of money and ceased following up on the pivot. It’s no secret that running out of money is the top reason for startup failures. Club Ovahi was bootstrapped. I funded it from my own savings, a couple of loans, and a grant. It made some income here and there but ultimately a lot more was needed in order to pursue the enterprise model. And a whole new Empathy stage was to be completed. Things didn’t line up, that’s when I called it quits in 2014 and moved on to another project.

Lesson 1: Find the One Metric That Matters (OMTM)

As mentioned earlier, the authors of Lean Analytics make a compelling case for early-stage startups to measure and track only one metric that matters. Vanity metrics should be thrown into the trash bin. In retrospect, our metric could have been: % of users who are active per merchant location. This metric alone has a lot of value since over time it would inform us about user adoption rates and location specific performance. It speaks directly to our business model and its increase over time indicates user acceptance and the coveted product-market fit. The metric can be used to convince customers and investors that the app is popular and is being used on a regular basis.

More importantly, the metric can guide decision-making and merchant targeting activities. It would’ve given us insights into the profiles of the merchants that we should pursue, and into new features that would enhance user experience and uptake.

The bottom-line here is that the OMTM should have guided us through the Empathy stage and ideally presented us with a “go, no-go” decision point, early on in the life of our company.

Lesson 2: The Devil’s Advocate is your best friend

The Nobel Prize winner and author of Thinking, Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman, is a renowned psychologist who pioneered the field of decision-making and behavioral economics. He found out that many entrepreneurs are in the grip of “delusional optimism“. “They overestimate benefits and underestimate costs. They spin scenarios of success while overlooking the potential for mistakes and miscalculations” (Source: HBR).

We were no exception. Make no mistake, this optimism is vital for someone to jump ship and start a new company, however, it needs to be checked and put in its place.

In hindsight, I wish we had a designated Devil’s Advocate. Although we had an assortment of well-meaning advisors, they were all the armchair type. Many of them didn’t dive deep into our issues or some were friends who gave us scrubbed feedback. What I would now do is recruit an advisor who is smart, experienced, and invested in my success. I would designate the advisor as a Devil’s Advocate (yes, give them that title!), and request from them to deliberately challenge the business on a regular basis. This advisor must work hard against the suppression of pessimistic facts or opinions. On a regular basis, this sort of advice would tame delusional optimism and hopefully lead to a better outcome (i.e. fail fast, or pivot to success).

You might say that advisors should do that anyway. Great, but the reality is that many startups have casual advisors who either offer superficial feedback or act as cheerleaders. Both of these types are dangerous.

Today’s winners

Today’s winning digital loyalty model emerged in the forms of Ritual and the Starbucks App. Pre-ordering, payment, and loyalty bundled in one. This model solved two very important problems: for the users, it was waiting in line, for merchants, it’s bringing in more business.

Users hate waiting in line, in fact, there is a whole body of research on why waiting in line is tormenting. And merchants love to sell more with short lines at the counter, that’s more real hard dollars. But they never told us that, or we didn’t read between the lines. Ritual was the one with the leap of imagination to see the problem and build a business around it. They mastered the Empathy and Stickiness stages.

Finale

As the saying goes: this was a great learning experience. As an angel investor, I meet startups on a regular basis. And I know that 60 to 90% of them will probably fail (depending on who you ask). I hope that our story can help a few of them avoid a prolonged failure, and maybe even succeed.