How Maple Leaf Angels Invested During the Pandemic

[Disclaimer: the analysis and views expressed in this article are solely my own unless stated otherwise.]

Maple Leaf Angels (MLA) just concluded a banner year, despite the pandemic (fiscal year ended on March 31st). Total dollar investments were 32% bigger than the previous year, making this one of the most active years in MLA history.

At the very beginning of the pandemic, MLA member investment sentiment was negative. At the time, most of our surveyed members expected to either reduce or pause their investment activities. However, things changed in surprising ways as time passed. This change more or less mimicked Canada’s broader VC activity, which also had a record-setting year.

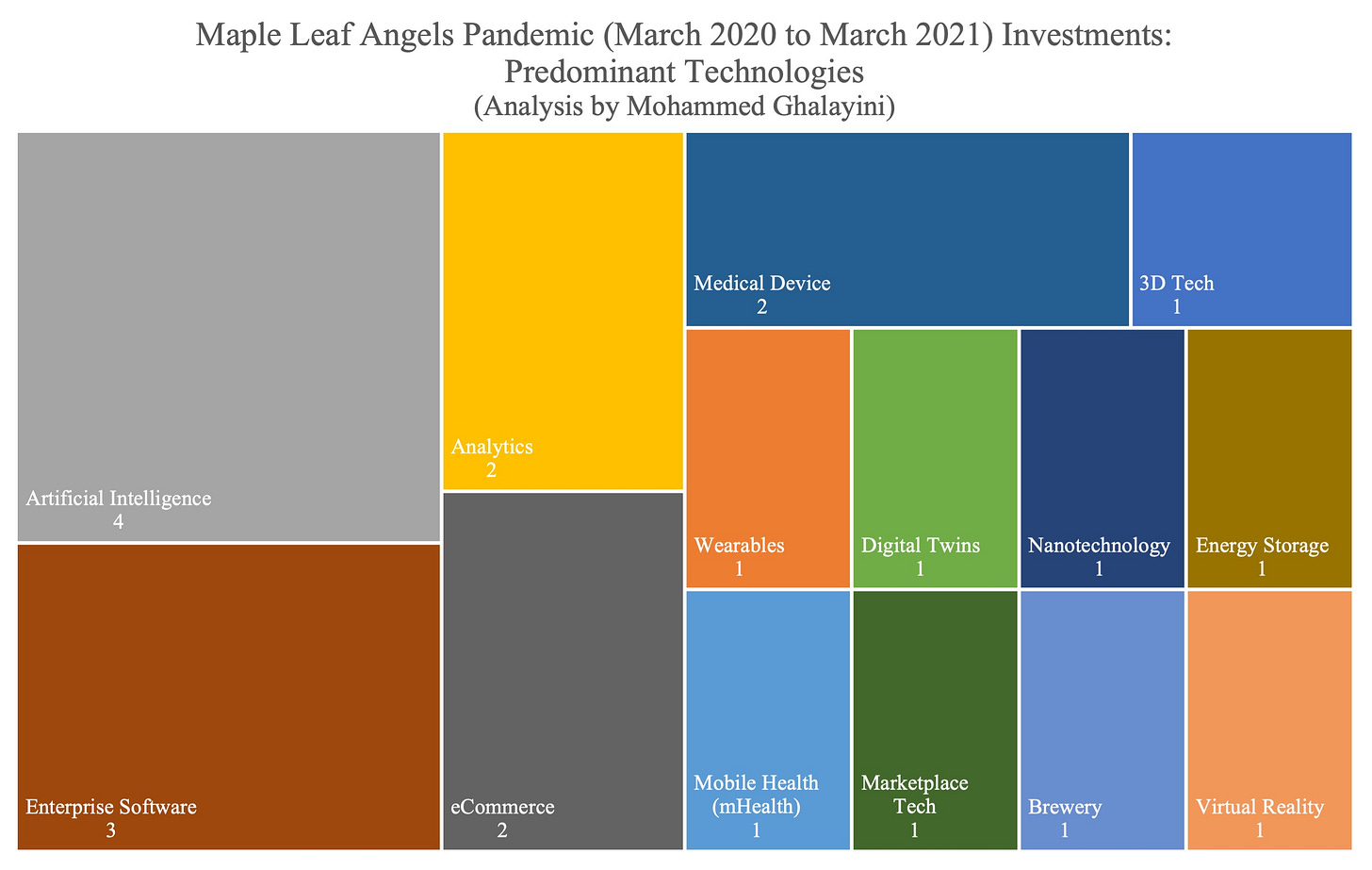

From March 2020 to March 2021, MLA invested in 22 companies. Healthcare led the pack by both dollar amount invested and by the number of funded startups. This matches previous years’ trends; healthcare tends to be the leading category of startups that MLA sees and invests in.

Artificial Intelligence and eCommerce startups were also popular this year; they both netted close to 40% of the total amount invested.

Notably, 26% of invested dollars went into existing portfolio companies as follow-on investments. This has also been the case within the general Canadian VC scene as funds scrambled to support and protect their investments.

Did the pandemic favour certain startups over others? The answer is mixed. Some startups like those in healthcare, education, and e-commerce showed pandemic-fueled traction, while others demonstrated long-term potential. Both scenarios attracted our investors.

Why was investment activity so high?

MLA’s transition to Zoom-based events was smooth and facilitated more participation. We found that more of our investors actively took part in our screening, evaluation, and due diligence processes, which must have positively impacted investment activity.

Like VCs, angel investors have long-term investment horizons and usually pre-allocate their venture investment dollars. Also, for accredited investors, the pandemic’s negative economic impacts may have been minimal, especially with massive market gains in equities, real estate, and other assets.

A rising tide lifts all the boats. In 2020, VC dealmaking in the US, according to Pitchbook, “remained incredibly resilient” and in Canada remained high, beating the previous five-year average.

And last but not least, the quality of the startups has just been phenomenal.

Great management team + Great product + Market validation

MLA members’ approach to investing has followed, perhaps unwittingly, the example of John Phillips, a Toronto-based lawyer who became an angel investor. In 2007, Phillips invested in Ottawa’s Shopify and, as a result, became a billionaire. From a Globe & Mail article:

Phillips was impressed by the "elegance" of Shopify's software and, using his simple formula of great management team + great product + market validation in the form of sales, had valued the nascent Shopify at $3 million and written a $250,000 cheque.

Phillips’ formula nicely sums up what MLA members look for. However, the focus on market validation invites the “too risk-averse” criticism. But a lot has changed over the past 5 years or so. Market validation doesn’t necessarily equate to sales anymore; our members invest in pre-revenue companies. Also, new early-stage VCs, tech-backed angel groups, venture studios, and angel-network funds (including the MLA48 fund) are adding dynamism and, as a result, “we are stepping up and moving up the risk curve.”

Ideally, the Canadian startup ecosystem should accommodate many investors with various risk appetites who invest at different startup stages. This should ultimately create healthy competition and positive FOMO. Counter-productive investors would be crowded out.

This will all need to happen while we navigate between two opposing narratives that are circling within the Canadian startup ecosystem: the overly optimistic one (“Toronto/Waterloo/Vancouver is the next Silicon Valley”), and the very pessimistic one (“the Canadian tech scene just doesn’t work”). The truth is probably somewhere in the middle. But that doesn’t really matter as long as founders keep on building and investors investing.